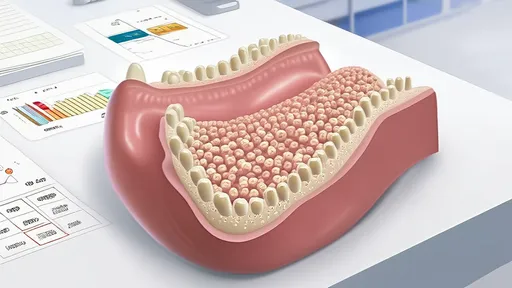

The human tongue is a fascinating organ, not just for its role in speech but also as the primary gateway to our sense of taste. Its surface, often described in terms of a "oral topographical map," is dotted with tiny structures called papillae, which house taste buds. Among the many variations in tongue anatomy, the texture of the tongue coating—often referred to as tongue fur or tongue moss—plays a subtle yet significant role in how we perceive flavors. When the tongue's surface becomes uneven, with patches of thicker or thinner coating, the way taste molecules interact with our taste buds can shift, altering our sensory experience.

Scientists have long known that the tongue's topography isn't uniform. Some areas are more sensitive to sweet tastes, while others react strongly to bitter or salty stimuli. However, the presence of an uneven tongue coating adds another layer of complexity. A thick, patchy coating may act as a barrier, slowing the dissolution of flavor compounds in saliva and delaying their contact with taste receptors. Conversely, areas with little to no coating may allow for immediate taste detection, creating an imbalance in flavor perception. This could explain why some people with significant tongue coating variations report muted or distorted tastes.

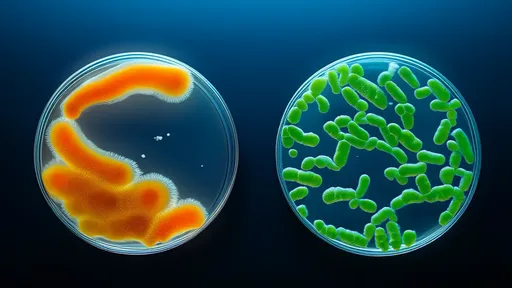

The biological purpose of tongue coating is still debated, but it likely serves as both a protective layer and a microbial habitat. The coating consists of dead cells, food particles, and bacteria, forming what some researchers call the "tongue biofilm." When this biofilm becomes irregular—developing raised or sunken patches—it may interfere with the even distribution of taste stimuli across the tongue. For instance, a deeply fissured tongue with accumulated coating in its grooves might trap flavors, prolonging certain taste sensations while blocking others. This phenomenon is sometimes reported by patients with geographic tongue, a condition where the tongue's surface appears map-like due to irregular coating patterns.

Beyond physical obstruction, the microbial composition of tongue coating may also influence taste. Certain bacteria metabolize food compounds before they reach taste buds, chemically altering potential flavor molecules. An uneven coating could create microenvironments where different bacterial colonies thrive, leading to localized variations in how flavors are processed. Some studies suggest that people with thicker tongue coatings perceive bitter tastes more intensely, possibly due to bacterial activity modifying bitter compounds into even more potent derivatives.

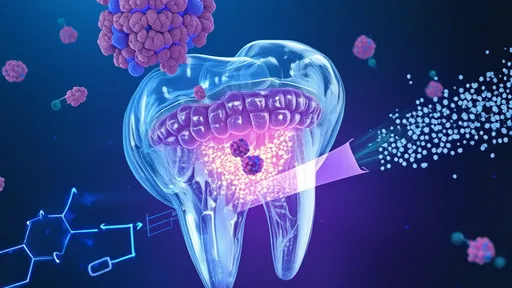

Clinical observations support the connection between tongue topography and taste perception. Patients undergoing tongue cleaning often report temporary heightening of taste sensitivity, particularly for subtle flavors. In traditional Chinese medicine, tongue diagnosis relies heavily on coating patterns, with practitioners correlating specific coating distributions with taste abnormalities. While Western medicine takes a more biochemical approach, the empirical evidence from multiple cultures suggests that tongue texture does play a role in gustatory function.

The relationship between tongue coating and taste isn't just academic—it has practical implications. For individuals with chronic bad breath (often linked to excessive tongue coating), the use of tongue scrapers doesn't just improve oral hygiene; many users report enhanced taste perception afterward. Chefs and sommeliers frequently clean their tongues to maintain optimal tasting ability. Even the food industry considers oral coating dynamics when designing products, as lingering coating from fatty foods can suppress subsequent taste detection, a phenomenon known as "flavor carryover."

Emerging research is beginning to quantify these effects. High-resolution imaging of the tongue surface shows how different coating distributions affect the spread of liquid flavorants. Computer modeling simulates how taste molecules navigate the peaks and valleys of a coated tongue. What emerges is a picture of the tongue as an active landscape, where physical texture and biological film work together to filter and modulate our taste experiences. Far from being a passive sensor, the tongue's changing topography makes each person's flavor perception uniquely their own.

Understanding these mechanisms could lead to better solutions for taste disorders. Patients with burning mouth syndrome, for example, often have altered tongue coatings, and therapies that normalize tongue texture sometimes alleviate taste disturbances. Similarly, elderly individuals experiencing taste loss might benefit from approaches that address age-related changes in tongue topography rather than just supplementing missing flavors. The tongue's terrain, it seems, is as crucial to taste as the taste buds themselves.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025